Sign language as “SWEET” and “HARD”: qualia and morality in Adamorobe, Ghana

Annelies Kusters

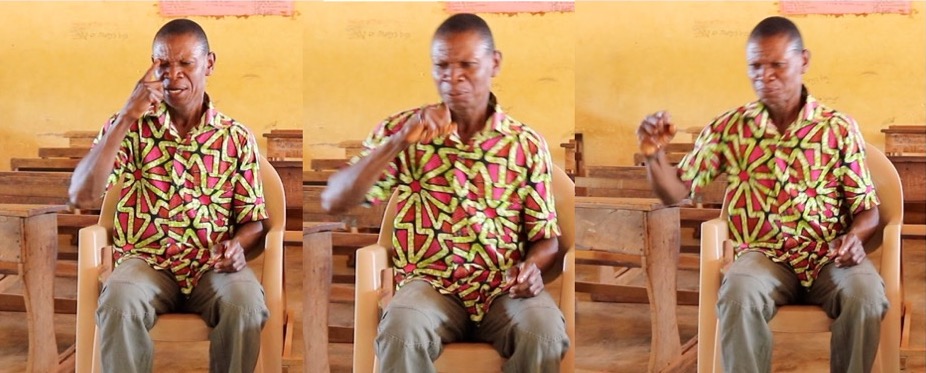

‘SWEET and DELIGHTFUL’, or ‘HARD’ are adjectives connected to Adamorobe Sign Language (AdaSL), a sign language used in Adamorobe, an Akan village in southern Ghana marked by a history of hereditary deafness. By calling AdaSL eg. SWEET (Picture 1) or HARD, deaf people in Adamorobe attribute qualia to AdaSL. Qualia are sensuous qualities such as sound, texture, taste, smell, shape, and spatial orientation. Examples of qualic evaluations are stink, warmth, hardness, straightness. For example, ‘lightness’ can be attributed to objects, human bodies, or language. In deaf Adamorobeans’ discourses, ‘hardness’ (as opposed to ‘softness’) can refer to deaf people’s social behaviour, to their bodies, but also to their language, AdaSL.

People can ascribe different qualia to the same language (Gal 2013). Calling AdaSL ‘SWEET and DELIGHTFUL’ is typical for most deaf youth from Adamorobe, who have gone to school for an extended period and acquired another sign language there, Ghanaian Sign Language (GSL). Seeing AdaSL as HARD and connecting it with being EYE-HARD (ie. confident) (Picture 2) is central in language discourses of deaf people over 31 (whom I will call ‘elders’, following local categorisations) who have had limited schooling and have limited command of GSL.

In this blog I show that sign languages can be evaluated in terms of qualia just like spoken languages. Secondly, within one community, there can be differences between qualic evaluations of the same sign language. Thirdly, qualic evaluations of signing are also evaluations of signers’ behaviour, and are thus inherently moral. Fourthly, these moral evaluations are expressed in the context of intergenerational differences involving different levels of formal education and bilingualism. The blog thus lays bare linkages between the themes of qualia, morality, generations, and bilingualism.

Picture 1: SWEET. Annelies Kusters ©

Picture 2: EYE-HARD. Annelies Kusters ©

Adamorobe: one village, two sign languages

Oral history locates the onset of hereditary deafness in Adamorobe in the late 18th-early 19th century. A relatively high number of deaf people was born there due to the circulation of a recessive gene for deafness through intermarriage. Deafness has been passed on through the generations, and while it is not the case that the majority of inhabitants is deaf, there is a sizeable deaf population. Currently 35 deaf people aged approximately between 10 and 80 reside in Adamorobe, a number which has been relatively stable over many years (see Kusters, 2015a). Its hearing population has recently increased starkly, and is currently numbering around 3500.

As a result of intense social-and kin relationships and interactions between deaf and hearing people in the community, a sign language gradually emerged and developed over time into a fully fledged language: Adamorobe Sign Language (AdaSL). Deaf people learned AdaSL and everything else from their (mostly hearing) parents and elders, including practical skills such as farming, hunting, trading, and house-keeping, and knowledge of traditional religion and herbal medicine. The 35 deaf people in the village meet and interact with hearing people on a frequent basis, e.g. greeting and exchanging news in AdaSL. Deaf people also regularly socialise in small groups consisting of deaf people only, in some particular outdoors spots in Adamorobe (see Kusters, 2015a).

In addition to AdaSL, deaf people in Adamorobe have been exposed to GSL on a regular basis through weekly church services and through short stints of schooling since the late 1950s, resulting in limited knowledge and use of GSL. Around the year 2000, almost all deaf children from Adamorobe were sent to a large residential school for deaf children in Mampong, where GSL is used in class and in leisure time. In 2018 (the time of my last field trip to Adamorobe), this cohort of 10 deaf children (now aged between 19 and 31) had ceased or completed school and 6 of them had children themselves. They are fluent in GSL and most of them are fluent in AdaSL as well, and they interact frequently with each other but also with deaf elders and with hearing people, using both AdaSL and GSL intensively on an everyday basis.

‘HARD’, ‘EYE-SOFT’

GSL and AdaSL are evaluated differently in qualic evaluations. In the process of qualic evaluations of languages, similarities are identified between languages and sensuous experiences. Through a process of repetition, these evaluations become conventionalised in language ideologies. Examples of qualic language ideologies are ‘hard words’, ‘plain speaking’, ‘talking straight’ (Gal, 2013). Deaf people in Adamorobe describe AdaSL as ‘HARD’, which is a gloss of a sign and its meaning does not entirely overlap with the meaning of the English word ‘hard’. It means that AdaSL is unique to Adamorobe and tough to understand for outsiders and even for many people within Adamorobe, which is a source of pride. ‘HARD’ also means clear, forceful, tough and expressive, and this is contrasted with the use of the body when signing GSL which is seen as weak and flabby (see Kusters, 2014). In 2008, the timing of my first extended field trip to Adamorobe, the deaf youth were still schooling and some deaf elders criticised schoolchildren who could not sign in AdaSL without a heavy GSL accent. Elders expected that youths’ AdaSL knowledge would ‘become HARD’ when the children grew older. Several deaf elders also found that deaf youth are ‘EYE-SOFT’ (Picture 3), meaning being shy, lazy, unengaging, reluctant and/or unconfident. In the context of communication, ‘EYE-SOFT’ means not calling people’s attention to chat, or not taking active part in conversations. These qualic evaluations of signing are thus embedded within a larger set of evaluations.

Picture 3: EYE-SOFT. Annelies Kusters ©

Signing and becoming ‘EYE-HARD’

Fast forward to 2018. Most of the former schoolchildren (8 women and 2 men) now live full-time in the village. Men did odd jobs and women were mostly focused on the household and their small children. They socialised more frequently with deaf elders than was the case when most of them were still schooling, using mostly AdaSL (but also GSL) with deaf elders, and mostly GSL (but also AdaSL) with each other. Deaf elders acknowledged that the deaf youth knew AdaSL well now: their AdaSL had become HARD. However, some of them insisted that the youth still sign ‘EYE-SOFT’, wishing that the youth would be more ‘EYE-HARD’ (the opposite of EYE-SOFT). When people sign in a way that is ‘EYE-SOFT’, their signing is not ‘SWEET’, not ‘DELIGHTFUL’. The sign ‘SWEET’ is also used to describe soft drinks and sugary food, and the sign ‘DELIGHTFUL’ is also used to describe food or a fresh bath, a fresh wind, or an activity that is enjoyed. In other words, signing that is ‘HARD’ and ‘EYE-HARD’ (in a clear, expressive and confident way) is a pleasure for others to look at, to be savoured through the eyes: they are adjectives not referring to AdaSL in itself, but describing goodAdaSL use.

Discourses about deaf people being HARD and EYE-HARD occur in a range of contexts, including stories about strong deaf warriors being the first deaf people in Adamorobe (Kusters, 2015b); and declarations about deaf people being strong farmers with ‘very hard hands’ and ‘very hard and very red blood’ that is ‘very good, strong and healthy’ in contrast to lazy, weak and soft hearing people’s bodies and blood (Kusters, 2015a). These discourses also occur in stories about conflicts with hearing people (such as inter-village conflicts and conflicts following discrimination of deaf people because of their deafness) which were brusquely and physically resolved by EYE-HARD deaf people (Kusters, 2015a). Deaf elders not only expect youth to make this shift to HARD AdaSL signing in an EYE-HARD way when maturing into adulthood, but also to be HARD and EYE-HARD in other ways.

The use of the signs EYE-HARD and HARD to refer to language use was thus embedded within this broader discourse about the nature of deaf people in Adamorobe, and deaf standards for right and wrong behaviour. Indeed, people morally orient to one another via qualia, which provide ‘aesthetic and moral anchors of orientation for reflexive, group-defining conduct and thus for the situated enactment of forms of personhood’ (Harkness, 2015: 576).

‘SWEET’/ ‘DELIGHTFUL’

Then how is the difference between AdaSL and GSL conceptualised, especially by the youth who use both languages extensively? In deaf elders’ discourses, ‘SWEET’ and ‘DELIGHTFUL’ is used to describe a particular style of AdaSL use (ie. mature signing that is ‘EYE-HARD’ and ‘HARD’), but deaf youths use it to indicate AdaSL itself. When I asked which language they liked to use and why, youths mostly said ‘AdaSL because it is ‘SWEET’/‘DELIGHTFUL’, in contrast to GSL which they said is ‘NOT SWEET’. Because of its expressivity, AdaSL was found more pleasant to use than GSL. For example, the signs representing days of the week are initialised signs in GSL (= signs based on the first letter of the day names, eg. M for Monday), as opposed to the AdaSL weekday signs which are based on events, history, and customs in Adamorobe. Thus, while GSL might be used most of the time amongst youth themselves, that does not mean it is ideologically preferred over AdaSL.

When I asked the youths what it meant that AdaSL was ‘DELIGHTFUL’, they started demonstrating. They recited core lexicon (WOMAN, MAN, FARM, SNAIL, OKRA). They performed how people talk to children (such as ‘Where is your mommy?’, ‘Where is your daddy?’ ‘Went to the farm?’). They demonstrated how people talk about illness, funerals and political parties. They explained and enacted how particular traditional dishes are prepared. They parodied the way other people dance, sign or argue, imitating people’s distinctive facial expressions and movements. In these long-winded demonstrations they emanated enjoyment, from time to time half-singing their examples in rhythmic ways, expressing the feeling of doing AdaSL. For them, ‘DELIGHTFUL’ also means funny: youth explained they laugh more when they use AdaSL than GSL.

Qualia and intergenerational differences

I suggest that the reason for differences in emphasis of youth and elders on AdaSL as ‘HARD’ or ‘DELIGHTFUL’ is that AdaSL plays a different role for them, even though both groups use AdaSL in the same or similar contexts in Adamorobe. Deaf elders foregrounded AdaSL as HARD, related to respect, authority, maturity, to deaf people’s strength and hardness, and to the need to be EYE-HARD. Deaf youth linked AdaSL to code-switching practices between AdaSL and GSL and enjoyment, foregrounding the feeling of doing AdaSL as SWEET and DELIGHTFUL.

Calling the language DELIGHTFUL is presented by youth as an important reason to use AdaSL not only with hearing people (including their own hearing children) but also with each other. Most of them insisted that they also use AdaSL with other deaf youth and not only with deaf elders, eg. one of them explained: ‘We often sign in GSL and when we get tired of it we switch to AdaSL’. In other words, they do not see AdaSL merely as indispensable to communicate with non-GSL signers in Adamorobe.

The continued existence of AdaSL is uncertain because the population of primary users (ie deaf people) is ageing, because the ‘deaf gene’ is no longer circulated intensively due to changes in marriage patterns, and because socialisation patterns in Adamorobe have shifted, leading to a general decrease in the frequency of AdaSL use with hearing villagers (Kusters, 2015). However, in Adamorobe, deaf youth’s linguistic enthusiasm for AdaSL (expressed in the ‘SWEET and DELIGHTFUL’ trope) was not negatively impacted by GSL proliferation, AdaSL language endangerment, and intergenerational conflicts between deaf inhabitants of Adamorobe.

In summary, the evaluation of AdaSL as well as moral behaviour and the nature of deaf people is uttered in terms of qualic evaluations such as ‘HARD’, ‘SWEET’ etc. Qualic evaluations tie together sensuous and moral evaluations of language use and behaviour across generations.

Acknowledgments

This blog is based on the journal article: Kusters A (2019) One Village, Two Sign Languages: Qualia, Intergenerational Relationships and the Language Ideological Assemblage in Adamorobe, Ghana. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology. doi:10.1111/jola.12254.

The author keeps the copyright of the blog text and images (Annelies Kusters ©).

References

Gal S (2013) Tastes of Talk: Qualia and the moral flavor of signs. Anthropological Theory 13(1/2): 31-48.

Harkness N (2015) The Pragmatics of Qualia in Practice. Annual Review of Anthropology 44: 573-589.

Kusters A (2014) Language Ideologies in the Shared Signing Community of Adamorobe. Language in Society 43(02): 139-158.

Kusters A (2015a) Deaf Space in Adamorobe: An Ethnographic Study in a Village in Ghana. Washington, D.C.: Gallaudet University Press.

Kusters A (2015b) Peasants, Warriors, and the Streams: Language Games and Etiologies of Deafness in Adamorobe, Ghana. Medical Anthropology Quarterly 29(3): 418-436.

Cite As

Annelies Kusters (2020) Sign language as “SWEET” and “HARD”: qualia and morality in Adamorobe, Ghana. Anthropological Theory Commons. url: http://www.at-commons.com/2020/03/02/sign-language-as-sweet-and-hard-qualia-and-morality-in-adamorobe-ghana/

About the author(s)

Dr. Annelies Kusters is Associate Professor in Sign Language and Intercultural Research at Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh. She has degrees in Philosophy, Anthropology and Deaf Studies and research experience in Surinam, Ghana and India. She currently leads a research team focusing on intersectionality and translanguaging in the context of international deaf mobilities, called MobileDeaf http://mobiledeaf.org.uk.